Flax Fibre: Production Process, Properties and End Uses [A to Z]

Last updated on October 5th, 2023 at 01:21 pm

Introduction of Flax or Linen fibre

Flax was probably the first plant fibre to be used by man for making textiles, at least in the Western hemisphere. Specimens of this fibre have been found in the prehistoric lake dwellings of Switzerland, and in the tombs of the Ancient Egypt. The evidence of biblical writings shows that the spinning and weaving of this fibre were well advanced thousands of years ago. Linen mummy-cloths have been identified as more than 4,500 years old.

This fibre comes from the stem of an annual plant Linum usitatissimum, which grows in many temperate and sub-tropical regions of the world. In the inner bark of this plant there are long, slender, thick-walled cells of which the fibre strands are composed.

During the seventeenth century, Linen manufacture became established as a domestic industry in many countries of Western Europe. Flax from Germany was the raw material for a flourishing linen industry that grew in the Low Countries. Linen manufacture spread from Western Europe into England, Scotland and Ireland, stimulated by the flow of French and Flemish weavers who were driven from their homes by religious persecution.

Until the seventeenth century only small amounts of this fibre were grown in England. Competition from wool had stifled the linen industry. The arrival of linen workers from France and the Low Countries created a demand for flax that was met by importation of the fibre, largely from Russia.

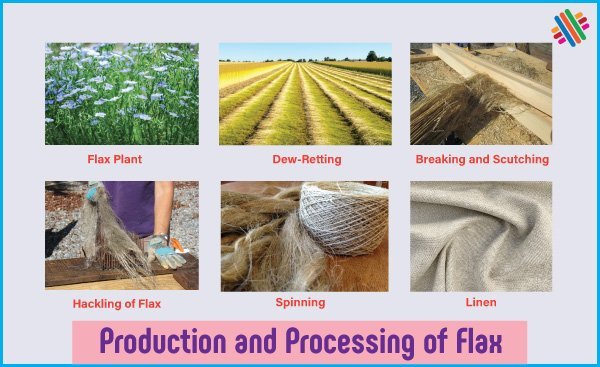

Production and Processing of Flax

Grown for fibre, the plant is an annual that reaches 90-120cm. It has a single slender stem that is devoid of side branches other than those which bear the flowers. When the plants have flowered and the seed are beginning to ripen, the crop is pulled up by the roots (by hand or by mechanical pullers). About one-quarter of the stem consists of fibre.

Retting

The fibres are held together in the stems by woody matter and cellular tissue, and ‘retting’ is a fermentation process that frees the fibres from these materials. Retting may be carried out in one of several ways:

Dam-retting

The plants after pulling are tied up in sheaves of ‘beets’ and immersed for about ten days in water in special dams or ponds dug in the ground. An obsolete method no longer practiced except in Egypt.

Dew-retting

The crop is spread on the ground after pulling and left for several weeks. Wetting by dew and rain encourages fermentation by moulds to take place. Dew-retting tends to yield a dark-colored fibre. It may be used in regions where water is in short supply; it is commonly practiced in the U.S.S.R. and France. This is the method by which some 85% of the West European crop is retted. It is far less labor intensive than water-retting and therefore less expensive.

Tank-retting

After harvesting, the seed bolls are stripped from the stems by reciprocating metal combs. The de-seeded straw, tied in bundles, is packed into concrete tanks which are filled with water and artificially heated to about 300 C. Retting is completed in about three days. Some of the best and most uniform fibre is produced by this process. Almost all of the flax from the Courtrai district of Belgium is tank-retted. The highest quality of straw may be double retted, i.e. the partly retted straw is removed from the tank, dried, and then given a further period of retting.

You may also like: A Guide to Wool Carbonizing Process

This fibre is brought in form a large area to be retted centrally in this way. The advantage of this form of retting lies in the fact that conditions can be controlled and the process can be carried out at any time of the year. In the Belgian method the straw is usually given a preliminary steeping treatment.

Chemical retting

Retting can also be carried out by treating the flax straw with chemical solutions. Such reagents as caustic soda, Sodium carbonate, soaps and dilute mineral acids have been employed with some success. In general, chemical retting of the straw proved to be a more costly process than biological retting and the fibre produced was no better. ‘Cottonization’ of this fibre is a form of chemical retting which is carried to the point where this fibre is separated into very fine strands. The flax can then be spun on cotton-spinning machinery. This was carried out in Germany and other Continental countries during the war.

Breaking and Scutching

The next stage in fibre production is breaking. The straw is passed between fluted rollers in a breaking machine, so that the woody core is broken into fragments without damaging the fibres running through the stems. The broken straw is then subjected to the process known as ‘scutching’, which separates the unwanted woody matter from the fibre. This is done by beating the straw with blunt wooden or metal blades on a scotching machine. The woody matter is removed as shive, which is usually burnt as fuel, leaving the flax in the form of long strands formed of bundles of individual fibres adhering to one another.

Hackling of Flax

After scutching the fibres are usually combed or ‘hackled’ by drawing them through sets of pins, each successive set being finer than the previous one. The course bundles of the fibre are, in this way, separated into finer bundles, and the fibres are also arranged parallel to one another. The long fine fibres are known as line. The tow is subjected to further combing or carding, which aligns the fibres more accurately alongside one another. They are then collected into the loosely-helped rope of fibre called a sliver or rove.

Spinning of Flax

Spinning may be carried out dry for the course yarns and wet for the finer yarns. In wet spinning the rove is passed through a bath of hot water. This softens the gummy matter holding the strands together, enabling them to be drawn out and aligned more perfectly as the rove is elongated and twisted during spinning.

Properties of Flax Fibre

The physical and chemical properties of this fibre are given below:

- Tensile strength: It is stronger fibre than cotton.

- Elongation: It is particularly in extensible fibre.

- Elastic properties: It is inelastic fibre.

- Specific gravity: 1.54.

- Effects of moisture: It has a regain figure of about 12%.

- Effect of heat: highly resistance to decomposition up to about 1200 C, when the fibre begins to discolor.

- Effect of sunlight: Gradual loss of strength on exposure.

- Effect of acids: It will withstand dilute, weak acids, but is attacked by hot dilute acids or cold concentrated acids.

- Effect of alkali: It has a god resistance to alkaline solutions.

- Effect of organic solvents: It is not adversely affected by dry-cleaning solvents in common use.

- Insects: It is not attacked by moth grubs or other insects.

- Others: It is a good conductor of heat; this is one of the reasons why linen sheets feel so cool.

End Uses of Flax Fibre

This fibre is used as:

- Sail and tent canvas

- Fishing lines and book binders

- Leather working thread

- Sewing and suture thread

- High-grade banknote

- Writing and cigarette papers etc.

You may also like: Cotton Vs Jute: Find the Key differences

![20 Natural Fibres in Textiles [2026] – Complete Guide](https://textileapex.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/textile-natural-fibre.jpg)

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My blog is in the same niche as yours, and my users would benefit from some of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this ok with you. Thank you.

I appreciate the effort and time you’ve spent in putting together this information. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Ready to have your mind blown? This website is a must-see!

I want to express my gratitude for your outstanding blog.Is there a way to re-trigger the confirmation email for my newsletter subscription?