An Overview of Batik Printing

Last updated on October 5th, 2023 at 07:28 pm

Definition of Batik

Batik is an Indonesian word describing a form of resist printing which, although known and practiced as a negative craft in south-east India, Europe and parts of Africa, has achieved an unrivalled degree of craftsmanship in the Island of Java.

It is a characteristic of Java Batik that the resist is obtained by applying wax to both sides of the fabric. Dyeing is then carried out in the cold medium to avoid melting the wax, thus confining the coloration to the unwaxed area. Selective further waxing and re-dyeing allows a variety of colorings of increasing depth to build up additively. Where complete color changes are required the wax is completely removed in boiling water and the washed and dried cloth rewaxed to cover those areas that it is desired to protect from further dyeing.

The Equipment’s Required to Produce Batik

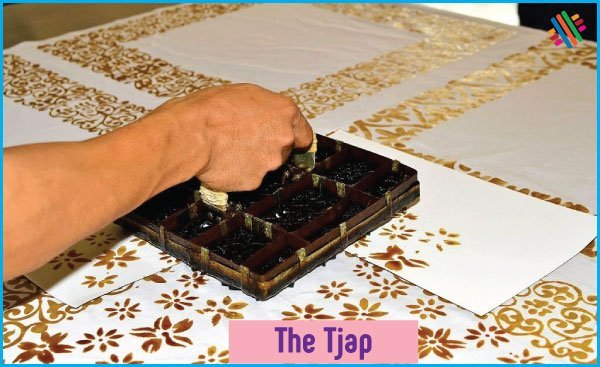

The Tjap

This is a specially made block composed of copper strips, hand-worked and fitted into a copper lattice, and held in place by solder. The all-metal construction allows its use in hot wax and the method of construction allows a completed block to be carefully sawn in two, thus forming a pair of mirror image ‘tjaps’. Printing of both sides of the fabric, essential in high class work, is thus not only possible, but also achieves a high degree of precision even in intricate designs. It may take a skilled craftsman up to a month to make a pair of ‘tjaps’. These blocks are seldom seen outside Java.

The Tjanting

This is a small cup made of thin copper sheet which carries a tubular spout at one end and it’s fitted into a short bamboo rod at the other by means of a rolled extension of the copper sheet which forms a fang. The joints are brazed and the spout, which decreases slightly in diameter to the delivery end, has a brazed seam. A skilled metal worker could fairly easily make a ‘tjanting’ for handicraft work, provided an authentic specimen were first examined and used to prepare a template. The diameter of the spout is varied to accord with the width of the line it is desired to trace and the very small bore ‘tjantings’ are naturally the most difficult to make and use.

Classical batiks were originally prepared by the daughters of Javanese nobility who worked diligently for many months on a single sarong using only the ‘tjanting’. Batiks produced in this way were outstanding examples of technique, comparable in pride of workmanship with the hand embroideries of their European sisters of former times.

The commercial production of batiks still occupies a considerable number of people in modern java. The basic design is normally applied by ‘tjap’ and the ‘tjanting’ used to complete the later stages and dyeing operation. Batiks produced in this way normally have rich but somber colorings with brown and oranges predominating. Indigo is used as a basis for deep shades of brown or blacks.

An alternate type of batik is characterized by striking designs of birds, animals or floral motifs executed in very bright colorings. These are produced in central Java by a slightly different technique. First the basic design is either stamped on by ‘tjap’ or hand drawn by ‘tjanting’. Afterwards, dyestuffs solution is painted over suitable areas using a small piece of bamboo fanned-out at one end to form a type of brush. In this way a design whose outlines were defined in wax, may receive a large number of different colors without a separate dyeing operation for each. When painting is completed the whole design area is covered with wax on both sides of the fabric using a fairly coarse-spouted ‘tjanting’. A background coloring to the whole design is then applied by dipping the fabric in a dye solution which penetrates all unwaxed areas.

Java batiks are normally marketed either in large oblong pieces which form the ‘sarong’ or in smaller square pieces to form a head cloth, ‘kain kapella’. Their designs, especially the use of border areas, have this end use predominantly in mind. Attractive European garments such as dresses, beach shirts, dressing-gowns and even ties can be made from sarong lengths.

The attraction of the batik technique in craft work is that by the exercise of patience and ingenuity excellent results can be obtained with little more than a ‘tjanting’. The choice of dyestuff is all-important or otherwise hours of work on the wax resist may be wasted. Particular attention has been given to choice of dye in the sections that follow.

Application of the Wax Resists

In making Java batiks, the cloth to be printed is first treated with a thin starch solution and ironed; this preliminary process improves the results and tends to prevent undue penetration of the wax into the cloth. Usually, the wax is printed on both the face and the back of the fabric, and the results are better if the wax is not allowed to penetrate the cloth but rather to form layers on the two surfaces. In this way the edges of the objects appear sharper in the final result.

Choice of Wax

In the production of java batiks the nature of the wax used is varied according to type of final effect desired. If a batik showing a ‘crackle effect’ is required, a resist consisting of a mixture of paraffin wax and resin is used. A suitable mixture is one of 4 parts of rosin with 1 part of paraffin wax, or 3 parts of resin with 1 part of paraffin wax should the rosin be high-melting variety. The higher the proportion of paraffin wax in the mixture the more brittle becomes the print and the more pronounced the ‘cracking’.

The wax-printed goods are allowed to hang for a few days and during this time the wax hardens and becomes more brittle. Should the hardening be incomplete the final ‘crackle’ effect will lack the characteristically fine veined effect which is the hall-mark of a high-class batik of this type. To increase the crackle effect the printed and dried pattern is sometimes worked for a short time under cold water to intensify the ‘crazing’ of the wax. Batiks showing a crackle effect are not normally required in java. They are more popular outside java than on the island itself and are often deliberately limited by mechanical means for the West African market by European roller printers.

The usual java batik has a clear resist showing no ‘crackle’ effects, and the wax used different from that employed for a batik showing a crackle effect. The Java batik is produced by block printing the designs on both sides of the fabric using two types of wax, each of which may have several components whose exact proportions differ from one batik printing establishment to another. The two main types are a light easily removed type consisting essentially of paraffin wax, and a darker more adhesive type consisting essentially of beeswax with some paraffin wax and an animal fat.

By the use on the same fabric of waxes having varying adhesive characteristics, different resist effects can be produced. For example, the printed and dried goods can be indigo dipped and then the light wax carefully shaved-off. This operation is performed by hand with the sarong suspended on a bamboo pole above the operative’s head. A crude scraper is used, often consisting of a hacksaw blade sharpened on the non-serrated edge. This is bent double and held in one hand, scraping being performed by the small piece of metal forming the bend.

Knowing the basic design required, the operative scrapes away the small areas subsequently to be over dyed. Next the goods are dyed in, for example, a direct cotton dyestuff using the ‘gosok’ technique and coupled in a suitable developer. At this stage the batik is examined and the hard wax printed areas repaired. Alternatively, further wax designs may be added by means of the ‘tjanting’ and the sarong overdyed again.

Printing Equipment’s

The cloth to be printed with the wax is stretched out on a table covered with layers of cloth; to prevent the hot wax from soaking into them the table cloth is sprinkled with an even layer of china clay or fine sand. In java, banana leaves previously soaked in dilute caustic soda are used as the wax will neither adhere to these nor penetrate into them.

The wax is applied from a special form of printing block. The wax is kept molten is a simple waxing vessel which is a shallow dish of sufficient size to hold the block. A piece of felt is placed in the bottom of this vessel, wax is poured over the felt and the whole is kept heated throughout the printing operation by a small kerosene lamp. The metal block, which retains its heat throughout the printing operation, is furnished as required from the surface of the felt saturated with molten wax.

Removal of Wax

The final operation in the production of java batik is the complete removal of the wax used as the resisting agent. This is carried out, after the dyeing operations described in the following page have been completed, by immersing the cloth in a bath of very hot or boiling water to remove as much as possible of the surface held wax, followed by a treatment in a hot solution of soda ash to remove the remainder.

The wax that is removed by hot water is skimmed off, collected, recast into blocks of suitable size and used again. That removed by the alkaline solution will be emulsified and cannot be recovered. Since the total amount of wax used in a batik represents a quite considerable capital outlay, no attempt is made to use alkali until as much as wax as possible has been recovered. This is one reason why genuine java batik has a characteristic smell of wax and rosin when first purchased, and this is retained for a considerable period after repeated washings.

Dyestuffs suitable for Use in Batik Printing

Dyestuffs suitable for this work must be capable of being applied from a cold dye bath, since a heated dye bath would remove the wax resist. The following classes of dyes are of interest:

- Indigo and other cold-dyeing vat dyestuffs.

- Azoic ‘Brenthol’ dyestuffs.

- ‘Procion’ dyestuffs.

- ‘Soledon’ dyestuffs.

You may also like: Flat-Screen Printing Method (Carpet)

I am curious to find out what blog system you’re using?